From Accasciato to Zwitser, there are thousands of types of cheese produced worldwide- 2018 saw 10.16 million metric tons of cheese made in the EU alone. This guide will bring you through the basics of cheese from how it’s made, how location can influence a cheese in the UK, and then finally we’ll go through how to describe the taste, texture and deliciousness of cheese. If you want to know a little more about how to build the ultimate cheese board- this is the place for you. Knowing where your cheese comes from, and what subtle variations in its production can have on the final taste, can bring you from intro to expert and really wow your guests. If you want to learn more about the processes behind your cheese, we’ve put together a step by step guide on each of the processes involved in cheesemaking. If you want to create a cheeseboard representing the best of British, you can skip ahead to our section on UK cheese regions, or if you want to know how to sound like a pro at your next dinner party-jump straight to the end for our cheese tasting notes section!

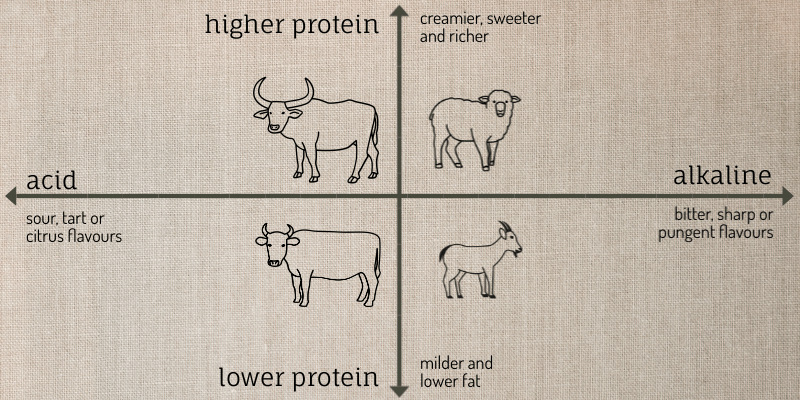

Cheese has been such a long-standing part of the human diet, that its development actually predates recorded history. Archaeological research has found evidence of cheesemaking as far back as the neolithic period. It’s no surprise that there are so many varieties of cheese out there! One thing, however, ties them all together- all cheese was once milk. ( Except, of course, vegan cheese) The most commonly used varieties are sheep, goat, cow and buffalo milk, but you can, of course, make cheese from any milk- one of the most expensive cheeses in the world is actually made from donkey milk. Historically, goat’s milk was most commonly used to make cheese as goats were easier to herd and feed. As humans settled into agricultural societies cows became the most common animal used in cheese production. As milk is such an essential component to cheesemaking, the type of milk used can dramatically affect the flavour of the final cheese. The primary difference in taste between different milks is actually the PH level- sheep and goat milk is naturally alkaline, whereas cow and buffalo milk are both slightly acidic. The fat levels in the milk will also impact the mouthfeel of the final cheese. Sheep and buffalo milk have higher levels of fat and protein, giving them a creaminess and a sweeter taste.  While the taste of cheese is heavily influenced by the variety of milk used, cheese is also impacted by the moisture levels retained in the cheese, its age and any bacteria that are introduced. These elements can all be controlled throughout the cheesemaking process, to create subtle variations in taste, smell and texture.

While the taste of cheese is heavily influenced by the variety of milk used, cheese is also impacted by the moisture levels retained in the cheese, its age and any bacteria that are introduced. These elements can all be controlled throughout the cheesemaking process, to create subtle variations in taste, smell and texture.

How Is Cheese Made?

Although there is huge variation in the subtle techniques used, the process of turning milk into cheese follows the same broad process. We begin with culturing the milk, to encourage bacteria to develop in the milk. The next stage is encouraging curds to form in a process called coagulation. The curds are then separated from the whey, using a variety of methods. Hard cheeses are warmed, in a process called scalding, whereas soft cheese is treated far more gently. The final stage in cheese making is the ripening and ageing of the cheese.

Culturing the Milk

This can be done with either pasteurized or unpasteurised milk. The milk is brought up to a specific temperature, dependant on the bacteria strain that the cheesemaker wishes to promote. If unpasteurized milk is used, the bacteria may be wildly present in the milk. Alternately, the cheesemaker might use a frozen or freeze-dried starter bacteria. This latter method is preferred when consistency is of high priority to the cheesemaker. The type of bacteria present during the culturing process affects both the taste and texture of the final cheese. Some bacteria produce only lactic acid during fermentation- these are homofermentative bacteria. The high acidity levels are ideal for imparting a sharp flavour, like that found in cheddar. Other bacteria produce multiple byproducts such as carbon dioxide or alcohol. These are known as heterofermentative bacteria and can be perfect for altering the texture of a cheese. The release of CO2, for instance, is how the gas bubbles- or ‘eye holes’ appear in much Swiss or Dutch cheese, such as Emmental. Heterofermentative bacteria also produce flavour compounds called ‘esters’ that can give a cheese a nutty or fruity flavour. Many cheesemakers will introduce multiple types of bacteria, often at different stages, to create a more nuanced and distinct cheese. Additionally, many types of cheeses such as soft bloomy rind cheeses or blue cheeses will have mould spores introduced in either this stage or later once the curds have been formed. Then as the cheese ages and ripens, the mould spores will develop in or around the cheese.

Getting Curds

This is the moment that the milk is intentionally curdled. The cheesemaker will check that the bacteria has developed enough during culturing to achieve the desired final effect, and will then prompt the process of the milk dividing into the solid curds and liquid whey. This is called coagulation. The protein and fat found in milk will group together into solid clumps, leaving behind the high water content of the milk. Milk with a higher water content such as cow milk will produce a higher relative amount of whey. The most commonly used method to start this process is the introduction of rennet. Rennet is an enzyme found in the stomach of many mammals, but calves are by far the most commonly used, with piglets coming in second. Rennet can also be made from plants such as nettles, figs or thistle to produce special vegetarian cheeses. The enzyme in rennet breaks down the milk by cutting the usual protein chain in milk which keeps the protein and fat suspended in the liquid. This allows it to form sturdy clusters of proteins and fat globules. Many soft cheeses don't require rennet at all, and instead use a variety of acids, such as lemon juice or vinegar to coagulate the milk. As opposed to rennet, this method will create very loose, delicate curds. The looser curd also results in high moisture, soft cheese often with an acidic flavour. Rennet will make a firmer, more robust cheese as it reacts in a different way to the proteins in the milk than simple acid coagulation. This is why many cheesemakers use rennet, as it allows them to add additional stages to adapt the final cheese after this step, without worrying about the curds falling apart.

Draining the Cheese

Much like it sounds, this is the process of draining the whey from the curds. There is a huge variety of methods that can be used for this. The simplest method is straining the curds through cheesecloth, which is then gathered together and hung. The longer you leave the cheese to hang, the firmer the texture you will be left with. For harder cheeses, moulds can be used. Specialist moulds are made for different cheeses. Moulds vary in size and shape and also have a unique combination of holes or slots to allow the right amount of whey to drain out over the right period of time. Moulds come in the form of either a basket, which can be a cylinder or square shape with a bottom or a cheese hoop- which is the same, except they have either no bottom or a removable one. Hoops can be more effective at draining out curds. Cheeses drained in moulds can either be left alone - Gravity drained - or will have weight applied and will be pressed. Often the cheese is turned over partway through this process to maintain an even texture throughout the whole cheese. While the primary use of hoops and moulds is to drain the curds, the cheese may also be aged in a mould to achieve a specific shape. When making fresh cheese, draining the curds is the final stage. Fresh cheeses are the simplest, and some of the oldest, types of cheese. The curds are gathered together and hung to drain in a cheesecloth. They can often be eaten the day they are made- Mexican Queso Blanco is usually drained for only a few hours before it is served. Fresh cheeses are often very mild in flavour with high moisture content and very short shelf life. Higher moisture levels in the cheese will result in a lower shelf life, as the cheese will begin to decompose quicker. Not all cheese is made from the curds. Some cheeses are actually whey cheese- the most well-known variety being ricotta. Here the whey from making other types of cheese- such as mozzarella, is used and the remaining milk solids are extracted from it. The whey is heated and salt and citric acid are added to encourage more curds to form. The yield for a whey cheese is much lower due to the lower milk protein content.

Scalding

Scalding is used after the curds have been drained to express even more whey from them. The curd is cut into smaller pieces and slowly heated, it is then placed to cool on screens to allow extra whey to drain off. Not only does this dehydrate the curds, but it also increases their acidity levels. To further increase the acidity and firmness of the cheese, a cheesemaker may use the cheddaring process. Once all of the whey from scalding has drained off, the curds are cut into strips and turned regularly. Turning the curds helps the whey to drain out, slowly creating firmer and firmer curds. After cheddaring is complete, these curds will then be milled down into very small strips and have salt added before being pressed into a mould.

Ageing & Ripening

This is where the unique flavour of the cheese really develops. During this stage, temperature and humidity must be very carefully controlled as the cheese develops. This need for extreme consistency is why the ageing and ripening of cheese has historically placed such high importance on local cellars and caves. Now with refrigeration, this is less important- but many traditional cheesemakers continue to use these historical methods. The time needed to ripen or age can vary from weeks to years depending on the type of cheese being made. As mould is living, it changes the cheese far more quickly than the ageing of hard cheeses, which is a process that can take several years. To control the development of bacteria during the ageing and ripening process, many kinds of cheese are brined in a saltwater or vinegar solution- often a mix of both. In the UK, it is traditional to wrap cheese in cloth to lower moisture content during the ageing process. The lower the moisture content desired in the final cheese, the longer the brining process will take, as the salt draws moisture out form the cheese. If mould spores were not added with the milk, mould-ripened cheese may be sprayed or bathed in water containing spores. Cheese can be either ‘surface-ripened’ where the mould develops only across the exposed surface of the cheese, as with brie, or internally ripened. To internally ripen cheese, the cheese is punctured to allow air through to the centre. This is usually done with metal needles- traditionally copper, but now often stainless steel needles are driven into the cheese to allow air to enter and distribute the mould spores more evenly through the cheese.

Many kinds of cheese can only be made in certain locations. This is largely due to the huge variety of local conditions that can affect the taste of the final cheese. The flavour of cheese can be dependent on the local weather and climate, specific cave structures, local bacteria, soil, dairy animal feed and happiness- not to mention locally varied breeds. On top of these physical characteristics, there is also the importance of local history and culture that goes into becoming an artisan cheesemaker. In the UK there are several varieties of cheese that have Protected Geographical Indication (PGI) status. This means that the location they are made in is so significant to the final product that only cheese made using specific practices within the defined area can bear the name. These special cheeses can be found in the following areas; Scotland, Northwest, Yorkshire, Midlands, Southwest and Wales.

Many kinds of cheese can only be made in certain locations. This is largely due to the huge variety of local conditions that can affect the taste of the final cheese. The flavour of cheese can be dependent on the local weather and climate, specific cave structures, local bacteria, soil, dairy animal feed and happiness- not to mention locally varied breeds. On top of these physical characteristics, there is also the importance of local history and culture that goes into becoming an artisan cheesemaker. In the UK there are several varieties of cheese that have Protected Geographical Indication (PGI) status. This means that the location they are made in is so significant to the final product that only cheese made using specific practices within the defined area can bear the name. These special cheeses can be found in the following areas; Scotland, Northwest, Yorkshire, Midlands, Southwest and Wales.

Bonchester cheese Must be made from the unpasteurised milk of Jersey cows grazing along the borderlands of England and Scotland, where their diet consists of herbs, hay and grasses. Bonchester Cheese has seasonal production between April and December, as the colder spring months affect the grass available for grazing. Teviotdale Cheese Made in the same region as Bonchester cheese, Teviotdale cheese is made in the autumn months in preparation for Christmas demand. Teviotdale is a hard cheese with a white crust made from unpasteurised milk. Orkney Scottish Island Cheddar Made with wholly Orkney island milk using a traditional recipe and techniques. The impact of the gulf stream on the Orkney islands produces uniquely rich milk. The cheese is also unique among cheddars as it is made using a ‘dry stir technique’ where the curds and whey are stirred after rennet is added, rather than being allowed to settle. This means that when the cheese is melted, less of the oils are released. Traditional Ayrshire Dunlop After being exiled to Ireland for her presbyterianism around 1660, Barbara Gilmour (later, Dunlop) learnt the recipe for this cheese. Returning to Ayrshire after 1688 she brought it with her, and this cheese was made in the region for years to come. The cheese itself uses milk from Ayrshire cows with a high level of butterfat- creating a rich, yellow cheese.

Beacon Fell Traditional Lancashire cheese This cheese can only be produced in the Fylde area of Lancashire. The softness of local water, consistent climate and abundant rain make for good grazing for local cows, which imparts a buttery flavour to the cheese.

Beacon Fell Traditional Lancashire cheese This cheese can only be produced in the Fylde area of Lancashire. The softness of local water, consistent climate and abundant rain make for good grazing for local cows, which imparts a buttery flavour to the cheese.

Swaledale Cheese The techniques behind making this cheese were taught to local farmers by monks who came across from Normandy in the 11th century, and was made using cows milk from the 17th century onwards. Once a commonly found cheese recipe in the Swaledale area, the recipe is now only known to the cheesemakers of the Swaledale Cheese Company. Swaledale Ewes Cheese Made by the same farm, using the same recipe as the above Swaledale, but using ewe’s milk, as was originally used in the 11th century. The sheep graze upon Yorkshire’s Hay Meadows, rich in biodiverse wildflowers. Yorkshire Wensleydale While Wensleydale can be produced anywhere, Yorkshire Wensleydale can only be produced near Wensleydale in North Yorkshire. If you're looking for a gift hamper containing Yorkshire cheese, check out our cheese hampers.

Swaledale Cheese The techniques behind making this cheese were taught to local farmers by monks who came across from Normandy in the 11th century, and was made using cows milk from the 17th century onwards. Once a commonly found cheese recipe in the Swaledale area, the recipe is now only known to the cheesemakers of the Swaledale Cheese Company. Swaledale Ewes Cheese Made by the same farm, using the same recipe as the above Swaledale, but using ewe’s milk, as was originally used in the 11th century. The sheep graze upon Yorkshire’s Hay Meadows, rich in biodiverse wildflowers. Yorkshire Wensleydale While Wensleydale can be produced anywhere, Yorkshire Wensleydale can only be produced near Wensleydale in North Yorkshire. If you're looking for a gift hamper containing Yorkshire cheese, check out our cheese hampers.

Stilton Can only be made in Derbyshire, Leicestershire and Nottinghamshire using pasteurised local milk. Buxton Blue A close relative of stilton, but can only be made in the area near Buxton in Derbyshire. Buxton Blue gets its flavour not only from the taste of local cows milk but from the hyper-local bacteria that form the starter culture. The cheesemakers have lived in the area for many generations, and as such the techniques involved in making Buxton Blue have been passed along generationally. Dovedale Cheese This rich blue cheese can also only be made in Derbyshire, within 50 miles of the town Dovedale that gives it its name. This is due to the combination of local knowledge and local yeast, bacteria and mould strains. Staffordshire Cheese A crumbly, semi-hard cheese with a citrusy finish, this cheese is made with a technique that Cistercian monks brought to the area when the settled at Leek in the 13th century. The large percentage of herbage in the cows' diet also contributes to the cheeses distinct taste.

Single Gloucester Can only be made in Gloucestershire county, with milk form the now rare breed the Gloucester cow Dorset Blue Vinny Cheese The protected status of this veiny blue cheese is connected largely to local history- cheesemaking tools have been found in Dorset dating back to 1800BC, and the word Vinny itself is derived from the 17th-century word ‘vinew’ describing a specific type of mould. Exmoor Jersey Blue Cheese A buttery blue cheese that owes its unique rich flavour to the warm, wet climate of West Somerset. West Country Farmhouse Cheddar While Cheddar can be produced globally, Farmhouse Cheddar can only be made in Dorset, Devon, Somerset and Cornwall. As the area that originated this popular cheesemaking style, there is a huge wealth of traditional knowledge and cheesemaking techniques that combine with the excellent dairy soil and the unique microclimate of each dairy.

Single Gloucester Can only be made in Gloucestershire county, with milk form the now rare breed the Gloucester cow Dorset Blue Vinny Cheese The protected status of this veiny blue cheese is connected largely to local history- cheesemaking tools have been found in Dorset dating back to 1800BC, and the word Vinny itself is derived from the 17th-century word ‘vinew’ describing a specific type of mould. Exmoor Jersey Blue Cheese A buttery blue cheese that owes its unique rich flavour to the warm, wet climate of West Somerset. West Country Farmhouse Cheddar While Cheddar can be produced globally, Farmhouse Cheddar can only be made in Dorset, Devon, Somerset and Cornwall. As the area that originated this popular cheesemaking style, there is a huge wealth of traditional knowledge and cheesemaking techniques that combine with the excellent dairy soil and the unique microclimate of each dairy.

Traditional Welsh Caerphilly This hard, crumbly white cheese is the only native cheese of Wales. Traditional Welsh Caerphilly has a higher moisture content than caerphilly that is mass-produced outside of Wales, can be eaten much younger, from only nine days old, and has a fresh, lemony taste.

Traditional Welsh Caerphilly This hard, crumbly white cheese is the only native cheese of Wales. Traditional Welsh Caerphilly has a higher moisture content than caerphilly that is mass-produced outside of Wales, can be eaten much younger, from only nine days old, and has a fresh, lemony taste.

Cheese Tasting Notes

Words used to describe cheese come partly from the scientific field of sensory analysis, partly from cheesemakers developing a language to communicate the traits they are trying to develop or avoid, and finally from thousands of years of humans eating cheese and wanting to talk about how great it is. From amateurs to professionals, we’re all connected by our love of cheese. But with such a large variety of sensations to describe- a gooey blue is a very different experience to a nutty parmesan- it can be hard to know where to start. With this in mind, we think it's easiest to break down the way we talk about cheese by the different senses- the main three being the appearance of the cheese, the aroma of the cheese and finally the flavour. When tasting cheese, it’s best to try the cheese at room temperature so that your palette doesn't have to wait for the cheese to adjust to your body temperature. Additionally, try and work from the lightest and most delicate cheeses to the most intense to avoid overwhelming your tastebuds. last

Looks & Touch

The most simple way people define cheese is by its colour. Colour is a sensory experience we have quite a large shared vocabulary for so the descriptions tend to be self-explanatory. Cheese may be described as being pale hay, chalky white or even deep yellow. Some cheeses are more than one colour, and veins in cheese will often be described in terms of their colour and density. More complex is how we describe the texture of cheese; which is a mixture of how it looks and how it feels. The broadest categories to describe the texture of a cheese relate very directly to its moisture content; soft, semi-soft or ‘buttery’, semi-hard and hard. More specific words include coarse, crumbly, elastic, fibrous, firm, flaky, grainy, hard, moist, rubbery, soft, smooth, sticky, or less appealing words such as mealy, oily, pasty and waxy. Many cheese connoisseurs use words such as “friability” or “adhesibility” to describe how the texture of cheese might change as you eat it. Friability describes something that crumbles into smaller pieces under pressure, whereas adhesibility is used for a cheese that evenly squishes as you eat it. The texture of cheese doesn't just change in the eating though- one of the most alluring things about cheese is, of course, melting it. Heating cheese will cause the oils to separate from the rest of the cheese, and the rate at which this occurs will impact the appearance of the melted cheese. Some cheese, like mozzarella, has a lot of stretch and elasticity when melted that it retains when cooled. Cheeses like Gruyère, however, will melt very evenly to create a sauce- which is why it is the most common cheese used in fondue. Other cheeses may melt smoothly but with extended heat crisp and crinkle. Or they may change very little in form when melted, and simply crisp at the edges, like halloumi.

Smell & Taste

Smell is a component of our sense of taste and is not to be overlooked. It almost always also precedes our tasting of food, as we will smell the food as it is raised to our mouths. It's always worth taking a moment to smell a cheese before eating it to allow you to more easily separate out the impact of these experiences. A cheese may smell a lot stronger or milder than it tastes, for instance. Cheese is said to have eight major aroma families: lactic, vegetable, floral, fruity, toasted, animal, spice, and “others.” "Lactic" smells or flavours might be tangy, biting and astringent, perhaps the cheese may even smell of sour milk. "Vegetable" smells may include perhaps a vague “earthy” smell, whether that be the smell of a forest or more like a damp cellar. Other more direct scent words used include “garlicky”, “oniony” and “mushroomy” which refer to the cheese smelling or tasting much like each respective item. A "floral" cheese may smell like fresh flowers, or perhaps a more intense, perfumed flavour bordering on soapy. Fresh apple, melon or peach are common fruity smells associated with cheese. “Fruity” is also often used more broadly to describe a bright sweetness. “Fermented” smelling cheese may be reminiscent of old fruit, wine or beer, but often refers to a cloying, aged fruit smell. "Toasted" refers to a sweet or savoury toasted smell. Used sometimes to directly reference toast, but more often is suggestive of baked goods generally. “Yeasty” is a common word used to describe a smell like fresh bread. Words like “biscuity” and “nutty” both refer to the smell of those items being gently toasted in an oven. This scent association is most likely to do with the Maillard reaction- the chemical reaction that causes food products to brown. "Animal" is a broad family of smells, that may not often sound appealing. “Barnyardy”, and “funky” both refer to a not necessarily unpleasant association that the smell has with farms. The smell is perhaps intense, and pungent but strangely attractive. “Gamey” describes a rich, fairly meaty smell. A strong, older goats cheese may very well be described as gamey. "Spice" can often refer to specific spices or to the feeling of chilli hitting the back of your nose or throat. Many kinds of cheese do not have spices added while being able to produce ‘spicy’ smells as a result of their starter culture. “Others” is the broadest category, but there are a few notable mentions. “Fresh” and “crisp” are often used as descriptive words for scent, that tend to refer very generally to a light, delicate or almost absent aroma and “Ripe” is often used to describe a noticeable but pleasant aroma. Finally, “unbalanced” is a broad word to describe one of these scent families being overpowering.